“When can I return to my normal activity after experiencing an episode of severe low back pain?” is a question I am often asked as a physical therapist. Low back pain (LBP) can be so severe and debilitating that it can completely derailing your training and lifestyle! It’s hard to run, exercise or even move if your back, buttocks or leg hurts. You either won’t try or if you do, you suffer through it only to be rewarded with worsening symptoms later on. However, in spite of what your back pain is telling you, initial activity and exercise are critical when treating LBP.

Everyone’s experience with low back pain is different and the severity of pain can vary wildly. For some, even walking normally can be difficult. This is why having a guide on which exercises and movements to do and not to do is so important. One critical indicator that you’re ready to taper back into more regular activity (as you progress your rehabilitation-based exercise) is whether or not you can walk with a normal gait. In particular, can you walk normally with a longer stride length during your normal gait cycle?

The ability to walk normally (notice that I didn’t say without discomfort) is an important milestone as it means that the spine is being stabilized well enough from the core musculature and that the nerves in the leg are not too tight or inflamed to tolerate and accommodate for the stretch that will occur from other activities.

If you are unable to walk normally, then the emphasis should be on regaining lumbar and lower extremity range of motion in addition to performing core and lumbar stabilization exercises. Limit your sitting, but do not try to taper back into other activities (at least not yet).

It is critical to remember that everyone’s recovery will be different. Recovery and tapering back into your normal activities should be entirely symptom dependent. Listen to your body on what it can handle. The pain will tell you if you need to stop.

When to Return to Activity after Experiencing Low Back Pain:

Follow the rule of thumb for movement: If the pain worsens by spreading peripherally down the buttock and into the leg and/or foot, then the condition is worsening. You must stop that activity. If the pain centralizes and returns back toward the spine (even if the pain worsens slightly), then keep moving as the condition is actually improving.

- Don’t resume your running, jogging or other training activities until you can walk normally at a quick pace.

- Be sure to slowly taper back into your training as your back begins to feel better. Don’t quickly resume your prior training volume. Instead, taper back up.

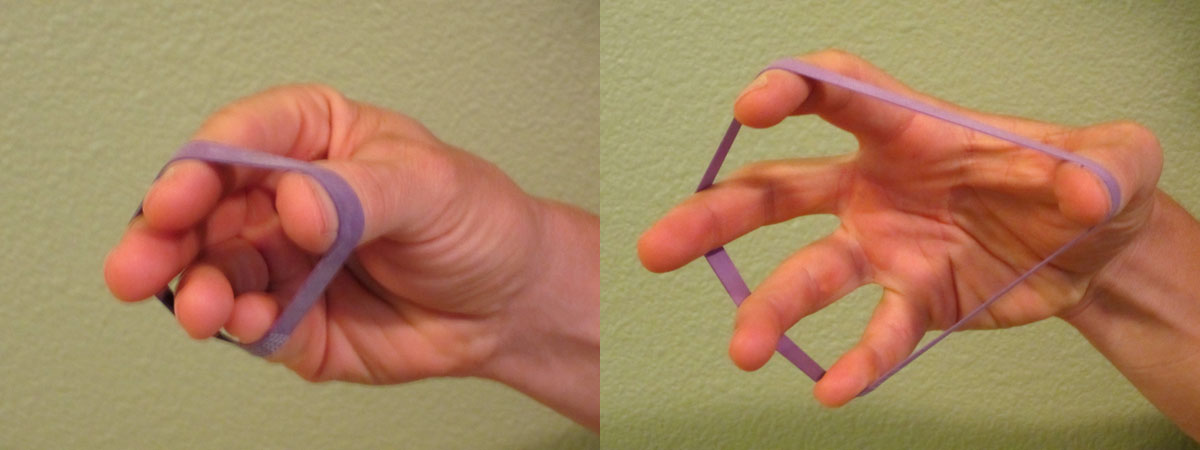

- Prior to activity and training, perform a very thorough warm up (including press-ups, superman exercises, and bridging). Then transition into an activity specific warm up.

- Continue with a core and lumbar strengthening program at least until you resume your full volume of training.

Prior to returning to your full and normal training activities, insure the following:

- Complete lumbar mobility has returned.

- You no longer have sensations, weakness or instability within the spine.

- If you experienced leg pain, your involved leg is as flexible as the other. The pain is now either gone or centralized (meaning that you’re not experiencing pain in the leg).

- Your hip mobility on both sides is equal.

- Your involved leg is as strong as the other leg, particularly hip abduction (glutes medius) and the hip external rotators. Test this by jumping up and down on one leg. Do you feel strong? Is there pain associated with this? If the strength isn’t there or the pain remains, you are not ready to taper up to full training activities.

- You can jog, run, sprint, and jump without pain.

With proper treatment, low back pain (LBP) should resolve in as quickly as two weeks. Severe episodes can take 4-6 weeks or longer. Continue with your rehabilitation protocol until you’re performing all exercises normally.

I highly recommend continuing with a lower extremity stretching protocol and lumbar and pelvis stabilization exercises as a method of prevention for future episodes of low back pain. There are countless “core” exercises and back stretches that you can perform, but which ones are best to help you to recover faster and experience less pain? Research is clear that performing proper core exercises and particularly, lumbar stabilization exercises are the most effective treatment modality for LBP. If you want to learn how to self-treat your low back and learn how to effectively exercise and work the core muscles in order to prevent or treat LBP, CLICK HERE.

AVAILABLE NOW ON AMAZON!

In my book, Treating Low Back Pain during Exercise and Athletics, you will learn how to address specific causes of LBP as well as the best practices on how to prevent and self-treat when you experience an episode of LBP. In this step-by-step LBP rehabilitation guide (complete with photos and detailed exercise descriptions), you will discover how to implement prevention and rehabilitation strategies to eliminate pain and get back to training and exercise sooner.

Learn how to prevent, self-treat, and manage LBP so you can get back to your daily life and exercise goals more quickly without additional unnecessary and costly medical bills!